Serena Lu Interview: Finding Your Identity After Retiring From An Elite Sport

Last Updated Jan 28, 2025

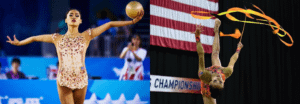

Serena Luis a former USA rhythmic gymnastics National Team member and a 2-time World Championships team member. She graduated from Princeton University in 2020 with a degree in Psychology and certificates in Dance and Cognitive Sciences. Currently, she works as a paralegal in the Major Economic Crimes Bureau at the Manhattan DA’s Office, and is an Apprentice with the NYC-based dance company, Movement Headquarters. Serena is also the current USA Gymnastics Rhythmic Athlete Representative and US Olympic and Paralympic Committee AAC Gymnastics Athlete Representative.

Serena Lu embodies the definition of a multi-hyphenate: a former USA National Team rhythmic gymnast, a dancer, a Princeton alumna, a coach, and a paralegal. Did we mention she’s only 23?

Her long list of accomplishments comes as no surprise when you meet her. She’s poised, thoughtful, warm, and bright. But, she will be the first to tell you her journey with rhythmic gymnastics wasn’t as glamorous as it appears from the outside.

Unlike many rhythmic gymnasts who retire once they enter college, Serena paved a new path of her own. After graduating high school, she chose to continue her gymnastics career and enroll as a full-time Ivy League student. While the decision to attend Princeton was an easy one for her, the year to follow was full of trials, tribulations, and heartbreak.

Balancing an intensive course load, training full-time off-campus, and navigating young adulthood weighed heavily on Serena’s mind and body.

“For the first time I felt the mental exhaustion of being an athlete.”

Ultimately, she decided to retire from competitive gymnastics at the age of 20.

But, what happens after you retire from an elite sport? In our conversation, Serena emphasized how unprepared she was to experience the grief that comes with mourning a lifelong passion. She described it as experiencing a void when you’re suddenly done, like losing someone close to you. Plus, the need to rebuild your identity outside of the sport.

“There was a lot of sadness, anger, and frustration,” she says.

Dive into Serena’s powerful, honest, and captivating story.

On Wellhub, your physical and mental health comes first. Experience guided meditations, center yourself with yoga, tackle anxiety attacks, an dmore. No matter where you are in your journey, we’re here to support you every step of the way. Pick a planthat supports you — mind, body, and mood.

Let’s start where it all began. Tell me about your experience growing up as a rhythmic gymnast and discovering this passion so young.

Lu: “This is something that started out as a very pure kind of love, and probably one of the things I have been most certain about in my whole life. When I started, there wasn’t even the tiniest expectation that it would be such a huge part of my life and change it as much as it did. My sister and I were heavily involved in many other activities that kept us busy, but the running thread through everything we did was driven by a passion for it and our parents were incredibly fostering in encouraging that environment for us to grow up in. No words can really explain how special the sport was to me, and it was the place I escaped to when things were difficult in my personal life.

I am so lucky to have had something I was so passionate about because from a young age, I learned how to set goals and how to make sacrifices for those goals. It was by no means easy- I remember always missing out on a “typical” childhood because I was always training or traveling. And it wasn’t a straight road either; like the most intense kinds of love, it drove me to the limits of my patience at times and there were countless times where I was frustrated and wanted to give up. When I was 13-14, I would go home after training just crying and I would tell my mom I was too tired and didn’t think I could keep going. At that point, my family had recently moved to New York and the sport was getting much more serious as a Junior National Team member, and that pressure was huge for a kid to take on. In these moments of discouragement though, I think it was even more clear to me that I wanted to push through even though I was struggling to get through immense stress and pressure. That was really where the passion carried me through, and I learned to be focused and that has definitely helped me grow as a person in more ways than I can even acknowledge.

It’s interesting how it impacts my life now and how I approach the trajectory I hope to continue on. Having known what it’s like to have a professional career that is also fueled by a love for it, it has made me realize that this is a quality I prioritize in my life going forward. I also know that it is incredibly rare and a gift when you find something that aligns in that perfect of a way, but because it has been such a big part of the way I grew up, I’ll never lose the determination to build a career and life the way the sport did for me.”

Can you share some of your accomplishments in the sport you are most proud of?

Lu: “I was a USA National Team member from 2011-2018, 5-time USA National Bronze All-Around medalist, and USA Champion in the Ball event. Being a national team member allowed me to also travel internationally to compete for Team USA at the highest caliber World Cups and Tournaments amongst the greatest athletes across the world in this sport; one of the greatest career achievements for me is being a 2-time World Championships Team member. I was also a part of the gold-medal winning team at the Pan American Championships. A personal career highlight for myself was competing at the Summer Universiade in Taipei and qualifying for the ball and ribbon event finals, where I not only represented the USA but also my University.”

Looking back at your time competing on the USA National Team, what stands out to you?

Lu: “I loved and lived to perform, not necessarily to compete. No matter how difficult the preparation was leading up, I always had so much pride and excitement being a representative of the USA National Team. One of my favorite things about the sport that kept me around for so long was getting to be a performer; in a way, those were my roots since I was young and I had done so much in the performance sphere from acting to playing piano. A rhythmic gymnastics routine can be so artistically crafted and masterpieces of art, so while these were competitions that I was at, I never lost the excitement to share a story or image within my routines that just amplified on the world stage as a National Team member. I had a large role in choosing my music and I wanted to always share an experience with the viewers.

When I think back to it, the most memorable parts of the experience aren’t the specific details but the feelings associated with those moments. Nothing is more extraordinary than the adrenaline waiting to walk onto the carpet, and feeling all the nerves and tension fade away to pure excitement. And of course, there is the other unbeatable experience of just knowing you nailed your routine to the best of your ability and the pride and oftentimes relief that all the work that you and your coach have put in paid off.”

Was there a mantra or piece of advice that got you through the tough moments in training? How did you persevere through these times?

Lu: “I naturally am really stubborn and a perfectionist, so most of the difficulties I had in training were frustrations with myself and how much progress I wanted to be making. I internalized a lot of the external pressure into my self-worth. And this was negatively impacting my training at times because I became motivated by a desire to prove others wrong and mostly prove to myself that I was better than I allowed myself to think I was. So naturally my favorite phrase that my coach would always tell me before stepping on the carpet was “one step at a time”, which literally means to take it one movement at a time and not let go of attention in a specific moment, but also to be patient with the journey and move steadily towards a goal. It always gave me a sense of removal that I needed because I was overly critical of myself and every little thing and outcome.

I’d like to say that I grew to be tougher because of how young I was when I started, so that helped me get through consequential moments that tested my dedication. But these were shared moments that every athlete has, such as getting through injury, rejection, and both emotional and physical pain. For me, the hardest moments were when dreams you work your entire life for are not realized. I was never more devastated in my life than when a huge goal I worked for did not end up in success. In those times, it’s so difficult to take the entire situation out of context and look at the overall journey instead of one failure. I was fortunate to have an incredible coach who I knew supported me and teammates that always helped me back up. As I got older, the more I realized that what gets you through these moments is purely what you are doing for yourself, and how you can derive worth and purpose not on any other person’s definition but your own.”

I know it’s very rare for an athlete of your level to go to college while continuing training (outside of the institution). What was the decision like to go to Princeton? How was this transition?

Lu: “Going to Princeton was one of the easiest decisions of my life- I was considering other schools in a number of areas but once I learned I was accepted, I knew that this was the perfect place because of its close proximity to my training gym. At that time, I knew I didn’t want to be finished with the sport and there were things I had set out to achieve for myself. On the other hand, I also grew up in an environment that stressed the importance of education. Taking a gap year wasn’t really an option I considered at the time or knew a lot about, and as a side note I want to stress that taking a gap year is something I will highly recommend considering and wish I did. Because rhythmic is a sport that favors youth, I appropriated that standard across other parts of my life. I was scared of taking a gap year and being “older” than my peers.

Lu: “Going to Princeton was one of the easiest decisions of my life- I was considering other schools in a number of areas but once I learned I was accepted, I knew that this was the perfect place because of its close proximity to my training gym. At that time, I knew I didn’t want to be finished with the sport and there were things I had set out to achieve for myself. On the other hand, I also grew up in an environment that stressed the importance of education. Taking a gap year wasn’t really an option I considered at the time or knew a lot about, and as a side note I want to stress that taking a gap year is something I will highly recommend considering and wish I did. Because rhythmic is a sport that favors youth, I appropriated that standard across other parts of my life. I was scared of taking a gap year and being “older” than my peers.

College was different from high school though, and while not much changed with my schedule, I was pulled in so many other ways that I wasn’t ready for. I was used to having a packed schedule already, having gone to full-time public school and training 6 days a week, 5-6 hours a day. But I was not expecting such a strong feeling of isolation; rhythmic is not a supported sport financially or publicly by USA Gymnastics, and there are virtually no college programs that support it. So in a realm of pretty much the unknown where I had to make adjustments to my training, I also was facing new perceptions that were not the most advantageous at times. It is difficult embarking on something new and being alone in it, especially as a high-caliber athlete that does not experience the same support as some other sports do. I would go myself to get extra training in the school gym at 7 am on weekdays during the open gym hours, training in sneakers and with a small speaker. It was very lonely and I was constantly tired: from an increase in schoolwork, the 3-4 hour commute between the gym and school, and from being my own personal support system financially and emotionally.”

I can imagine being a full-time Princeton student while training at such a high level had its highs and lows. Can you give us a glimpse into what this experience was like?

Lu: “It really tested the limits of what I could handle, so in that way it brought me to the highest of highs and unfortunately the lowest of lows. At it’s best, I was doing everything I worked for and I had both school and sport in my life. But mentally, I was really stretched. Like I mentioned, there is something very lonely about being on a journey that is difficult to share with others. At school, I wasn’t really an “athlete”, because I wasn’t technically on a Princeton team. But yet, I had a schedule that demanded from me what high-level college athletes are supported for. So that was an isolating identity. I was also a student, but because I had to leave campus every day to train, I could never fully embrace the student life on campus. I would come back to campus around 11 pm every night and have a mountain of things to do. My social circle was very limited. I was also always on edge to be prepared to adjust to a new obstacle. There were so many moments when I was too exhausted to even feel all the pressure on me and had nothing else to do but push forward. I knew people were looking up to me for doing this, and I didn’t want to let them down.

I never was comfortable asking for accommodations in anything because I always wanted to prove I could handle it. There was one month where I was slated to compete 2 consecutive competitions, one in France and the other in Portugal. When we have linked events, because of the time difference we would often stay abroad to train for a week. I had a class that would not allow more than a specific number of absences, and after trying to propose a concept of video calling into class (back then this was a wildly unforeseen concept, who would ever video conference into a class), I ended up booking a flight back to school for just the day to make this class, and flying back to Europe that evening. It was both a huge physical and financial sacrifice that to many, seems like it wouldn’t be worth it. But these were things I didn’t think twice about making adjustments for, because they were equally as important to me.”

Can you walk me through your decision to retire? How were you feeling physically and mentally?

Lu: “In as few words as possible, I was honestly just exhausted. And that’s what was the most painful part of it; I never thought I would be so exhausted by something I loved so much. It really hurt admitting that to myself and to the community around me. I had been physically pushed the summer after my freshman year training for the Summer University Games, and the trip was wonderful and beautiful in many ways. The exhaustion only hit after arriving back home; it was a mixture of just plain physical tiredness, but also a feeling of hopelessness for why I was still trying to push myself in something that wasn’t getting minimum acknowledgment for. I think that comes from a culture of disposable athletes, which is something I have been really trying to push against. Athletics are extremely outward-facing, and while it may seem unimportant or trivial to acknowledge accomplishments or to show appreciation, to an individual who has made it their livelihood, these things can set apart an experience by so much. That made me bitter and even resentful at times, which I learned after retirement is sadly commonly shared by athletes.

I phased out of training to focus on mentally repairing myself; I had a very unhealthy relationship to my body and my self-esteem. The decision to retire came very unexpectedly, and I didn’t know it was happening until I physically sent in my retirement letter to the organization. It was almost a decision that felt made for me because breaks from this sport to focus on mental healing really never happen. Coming back to it, or even the option, didn’t feel encouraged in a way where I felt as at home in the sport as I did before I took a break. I tried training again before retiring, and it felt like I was an outsider looking in, which displaced everything I knew about myself. Being a stranger to it pushed myself further away from it just because it hurt so much to feel that way.

I never expected the actual retirement process to be so hard; one of the aspects that make it so difficult was that there is so little parting acknowledgement in that process either. A 15-year career can be faded away so quickly in that process, and I was left with no transition phase to rediscover myself in life. And I know it sounds so incredibly insignificant and nowhere as bad as I thought would affect me in the magnitude it did. But the things I pushed myself to do and achieve for what was my entire life at that point were important to me, and these were things that truly took incredible sacrifice and pain to achieve. I was hurt by how little it seemed like it mattered to those that claimed to support us, but largely because no matter what I did, I couldn’t see for myself that what I did was a huge accomplishment. I felt like I failed astronomically, and was never good enough. If anything, I hoped to have been a good role model like many before me were for me, and it felt like I had let everyone down. It was truly equivalent to suffering a loss of a loved one, one that I had loved more than anything. No one prepares for you that- and no one was really there to help navigate this abyss of broken pieces that make up your identity, and how to pick yourself up to walk the next part of life.”

After retiring, you described feeling a void and grieving this loss. Can you share some of the feelings you experienced during this time?

Lu: “It was the whole rainbow spectrum of emotions, honestly. I was so angry, sad, frustrated, apathetic, all of it. At the base of it all, the loneliness I felt being an athlete didn’t go away. I pushed myself to be around people and threw myself into the student life at school, but I never felt more lonely as I tried to transition out of it. There weren’t “athlete support groups”, although that would be a fantastic thing to be available for athletes. Even if there were support and transition groups offered for elite athletes, they were not openly extended to the majority. My close friends were still competing, and out of a fear that I would be a burden on them, I distanced myself. I was also so disappointed and guilty in myself not being able to just be happy for their accomplishments which were the exact ones I had worked for as well. There was so much regret directed at myself for not trying harder, and the shame of not achieving what I dreamed of. No one really knows what to do when you fall down hard from what seems like your entire life’s work. I didn’t want anything to do with the sport because it felt like the sport didn’t want anything to do with me.

In the whole transition of being a regular student, I definitely just floated around for a large part of it. I don’t know how much it seemed that way, but I was very lost. There was also this feeling that so little excited me as much anymore. I kept taking on more and more to match the level of personal thrill I got from being an athlete. It’s hard to know how to cope with loss of identity at such a magnitude. At first, I couldn’t even come face to face with anything related to the sport so I actively avoided it. The amazing people I met didn’t know me as an athlete, which was so surreal. It was so strange having these people in my life who had no idea what my previous life was like. One way to explain what it was like is watching a playback reel of someone else’s life. That entire year, this kind of dull nostalgia followed me everywhere.

I tried to keep as much of the process private to myself, because a main part of the recovery and healing process was to redefine my relationship to self and the relationship to the sport. I didn’t even want to talk about it to anyone until recently. I’m still working through it, because the pain from it still comes back in different forms. It is definitely a work in progress and can’t be rushed.”

If you could give 3 pieces of advice to someone going through retirement from a sport, what would you say?

Lu: “The first piece of advice requires there to be support systems in place, which is a separate issue. But I want to stress to anyone going through this process to engage in personal support systems and reach out to have conversations about the process. I thought being alone in it would do a favor to others around me, but it really disadvantaged me in many ways. There needs to be a healthy avenue to talk to someone about it.

I also would strongly encourage pacing after retiring from a sport. There is no rush to become so intensely involved in anything that quickly, and it’s important to take some time just for yourself. Being an athlete has trained me to always feel like I need to be achieving and working really hard for a goal, but never emphasized the importance of taking your time or self-care. In a way, that limited my courage to be curious about exploring other passions because I was strapped to finding the next thing to hold onto.

The last thing I would say, because I wish someone would have told me, is that it’s okay to feel all the range of emotions that come with it and to take your time with it. I felt like I was maybe doing something wrong to be distraught over it, and that maybe I was over exaggerating the experience. There was also a sense of shame I had for being so upset over it, and for taking so long to be okay with it. But the process takes time and there is no need to rush through it or take on any pressure to immediately find the next path. I was so scared to have an open road ahead and feared that I was behind in finding that, but everyone has their own timeline and there is something special in finding that on your own progression.”

You’ve already experienced so much life at a young age. What has your mental health journey been like? How have you found ways to practice self-care during stressful times?

Lu: “Because mental health is a topic that wasn’t as actively discussed until much later in my career as an athlete, I definitely harbored tendencies that negatively affected me as an athlete. The sport is so beautiful in many ways visually, but with an aesthetic base playing a large component of it, there were constant environments that my teammates and I found ourselves in that we normalized. Weight has always been a constant cloud over anything we did, and I look back on some of the ways we would discuss the issues and laugh it off. But no matter who you were in the sport, it affected your mentality significantly. I don’t want to gloss over the effect this had; I was terrified of gaining weight and developed a negative body image from very early on, almost exaggerated to an extent because I was told that the way my body was like when I was young was perfect for the sport. I was so scared one day I would lose that because naturally as you get older, your body changes. I would preemptively anticipate this happening, so I was constantly stressed and ate in ways that were not properly fueling my body. This unfortunately isn’t a unique experience, and it doesn’t just go away after you are done. The solution isn’t as simple as knowing you are a healthy weight, because our eyes have been trained to always want to see a thinner frame.

The hardest times were definitely when there was clearly a lot of pressure riding on your performance, which is natural for a high-stakes environment. Mental fortitude is a skill that just like other physical abilities, needs to be trained and fostered. This I realized much too late in my career, and wasn’t something as prioritized as it should have been when I was growing up in the National Team. We didn’t talk about the mental effects of being under constant pressure that a lot of us just put on ourselves more than anything. We had perfected our physical training regime in a way, but not the mental training. My teammates and I were just 15-16 years old, going to these huge competitions with expectations of ourselves to achieve incredible things and were afraid of letting everyone down. I didn’t ever have a strong sense of confidence, so I personally struggled a lot with learning how to be satisfied with my performances or feeling like I was just simply good enough. That kind of mental strength shows most in competitions, when the final piece of the puzzle is how you can go and just compete. And I think the environment we were in wasn’t always the most encouraging, so I took that personally and was so hard on myself all the time.

That is also a reason why I felt such a strong sense of failure after retiring, because I could not see the successes in my career or be proud of them. I always put those down in significance and could never be satisfied. It is such an externally validated sport that I carried this into my own self-worth beyond being an athlete. These are the scars that continue to re-emerge post-career and unfortunately I see them manifest in my life in different ways now. However, I am now in a much more stable position now to reconcile and acknowledge when it happens, and to deal with it in a much healthier way than before.”

Soon after retiring, you began to explore dance through Princeton’s resources. What role did trying this new art form have in shaping your post-retirement identity?

Lu: “To be completely honest, dance was the closest lifeboat I could grab onto right as I stopped training. It has many of the same elements as what drew me to rhythmic gymnastics, and I wanted to be a part of a community that was bigger than myself. I initially tried out for the dance companies at school casually because I had a close friend in one of them; I did not know what I was in for.

While I think back to it now and realize it may not have been what I did if I had felt okay taking time to try another interest, dance gave me so much. I realized things I didn’t even know I was missing out on. I found a really great community on campus that welcomed me and helped me adapt to being a student engaging in life at school. I realized that I still love performing and always will, which was a huge realization for me. There were definitely growing pains in joining another close-knit community with such a strong sense of identity. I think I wanted that so badly that I tried to fit myself to match and dove headfirst into it. But despite that, I loved the familiarity in it; I had something I was dedicated to and could work hard on, and goals I could set within it.

The dance department at school was something I found later in my time at school, which was such a gift. The resources available to us gave the students a one-of-a-kind experience working with inspirations in the dance community. These were artists that dedicated their lives to it and it was a pleasure being able to learn from them. The professors and guest artists that we worked with will always have an impact on me as an artist. So much of it was therapeutic as well; I remember vividly working with an amazing guest lecturer and doing so much work on letting movements initiate from a more grounded, internal source which is totally opposite from what it was as a gymnast. While it was challenging to essentially remold and relearn movement, I found myself less and less conscious of perfectionism and how it “looked” the more I danced in the department. It was really liberating after being trained to think of that all the time.”

You mentioned you’ve been finding new passions in your job, acting, and coaching the next generation of rhythmic gymnasts. What are you looking forward to as you navigate this new, post-grad chapter of your life?

Lu: “The spontaneity of life and the many different paths I am curious about is equally exciting and terrifying. I am very much still figuring it out and trying to be excited about that. I have pretty diverse interests and some may see it as I have no set path, but after having my entire experience growing up being so defined, this is relieving.

I’ve also been trying to actively take off the pressure from having a result-based approach to this next chapter. No matter what I do, I want to know for myself that there are aspects of it that I am passionate about, and that I am not in pursuit of solely a result. That way, wherever I end up will be the result of many different things that I was able to stay in the moment of and learn from. I missed so much of what made rhythmic gymnastics so special for me because I was narrowly focused on just the destination. And rarely does our intended destination work out exactly the way it is imagined, which caused a great deal of sadness for me in the past.

I’ve also been trying to actively take off the pressure from having a result-based approach to this next chapter. No matter what I do, I want to know for myself that there are aspects of it that I am passionate about, and that I am not in pursuit of solely a result. That way, wherever I end up will be the result of many different things that I was able to stay in the moment of and learn from. I missed so much of what made rhythmic gymnastics so special for me because I was narrowly focused on just the destination. And rarely does our intended destination work out exactly the way it is imagined, which caused a great deal of sadness for me in the past.

Everything I have been doing post-graduation has brought me fulfillment and taught me so much that I couldn’t honestly ask for more. My job has been incredibly rewarding as a first place to work after college, and it is inspiring working with people who have so much knowledge and passion for their field. I’ve also been able to continue my interests artistically which was a big step for myself personally. There is a risk that inherently comes with any career, but especially in the arts. Just being able to open up and admit that this is something I would love to pursue as a career has cleared some blocks I placed on myself.”

How has coaching young athletes been? Do you have any advice you share with these rising rhythmic gymnasts?

Lu: “When I first went back to coaching, it felt so strange and really awkward to be in the gym. I still felt out of place, like I was an imposter. It was not easy either; I’m pretty sure I cried every day coming home from coaching at first because I missed training so much.

The interesting thing about coaching from my perspective is being able to see, from a more outside view, similar experiences to my own as an athlete. Very little had changed in the narrative, and that hurt me to see these young athletes stepping into similar pitfalls. Having been removed for a bit from the sport before coaching but still fresh with the memory of being an athlete, I hope that I was able to impart some of my own experiences in a way that can help these athletes take a different approach. On the other hand also though, I got such valuable insight into the perspective of a coach and being in a different position in the sport. It’s funny to talk with my coach now about the frustrations you feel as a mentor, which I only understood after doing some coaching myself. I definitely had moments as an athlete where I was too stubborn to listen at times, especially in moments of high frustration. You want the best for these athletes, and so much communication and trust has to happen both ways for an effective relationship to work.

I also realized that I love coaching and being with these athletes who are so dedicated and focused. They are building such strong foundations for the rest of their lives, and I try to encourage that in a positive way. It’s nice to be back in the sport in this context, and coach in a way that I wish the sport outwardly supported more of. I find things like positive reinforcement to be the most helpful. I find it to be challenging intellectually at times even, and I think concepts I learned as a Psychology major come out in ways that I coach. But most of all, in my unique perspective as a recent athlete, my biggest goal is to relate to them more so they feel their experiences are valid. My advice tends to be related to the fostering of a passion and the journey towards a goal. Setbacks are common in a tough journey, and it is easy to make a momentary failure the end-all-be-all moment. I just want them to hear more reassurance and encouragement to continue, to persevere, and to acknowledge the successes even in these moments.”

Lastly, is there anything you would like to tell your freshman/sophomore year self?

Lu: “Honestly, there probably wouldn’t be anything I would have understood just hearing about it. I am glad I went through all that I did those two years, even though it was incredibly difficult. If there was one thing, it would probably be to just relax a bit and honestly to slow down. I was rushing constantly against who knows what. Whatever it was, age, time, or a self-induced definition of success at a specific point, I was always racing to the next thing. And because of that, I missed a lot of the journey which sounds incredibly cliche, but the journey really is a special part of life. Time passes so quickly and great experiences are meant to be lived in the moment.”

Category

Share

The Wellhub Editorial Team empowers HR leaders to support worker wellbeing. Our original research, trend analyses, and helpful how-tos provide the tools they need to improve workforce wellness in today's fast-shifting professional landscape.

Subscribe

Our weekly newsletter is your source of education and inspiration to help you create a corporate wellness program that actually matters.

Subscribe

Our weekly newsletter is your source of education and inspiration to help you create a corporate wellness program that actually matters.